Pequotsepos Brook Preserve by the Goodwin Niering Program

Nako Kobayashi

Moriah McKenna

May 7, 2015

The Avalonia Land Conservancy, based in the historic downtown area of Old Mystic, Connecticut, is an organization dedicated to preserving the natural and historic landscapes of southeastern Connecticut. One of Avalonia’s many historic preserves is Pequotsepos Brook, which closely borders the newly erected West Marine boating and sport supply store to the south and east. This forty-four acre property was once settled by Captain John Gallup, one of the first colonial settlers of the area and member of the original founding families of America. Pequotsepos Brook preserve is part of the five hundred acres of land that John Gallup received in 1643 from the royal court in England for his part in massacring the Pequot Indian Nation originally based in the area. The original Gallup land was bounded by the Mystic River to its west, Captain Stanton’s homestead to its east, and Captain George Denison’s land to the east and south. Parts of the land now consist of Coogan Farm, the Pequotsepos Brook preserve, and the historic Whitehall mansion, built on land bought from Lieutenant John Gallup in 1771, that still exists today as an inn. The last family to farm on the property was the Page family which included Frederick H. Page and his sons Donald L. Page and Henry D. Page. Using an obituary search, it is possible to learn more about this family and its history if you are interested. The area was known as the Page farm. This land was later sold and divided up by the developers, Maritime Park Associates for residential use in the 1950’s.

A book written in the 1700’s by Grace Denison Wheeler, describes the original Gallup homestead as being a quarter mile northeast of the historic Denison Homestead.There has been much speculation about the true location of the original Gallup home, as the ruins depicted in an old photograph in Grace’s book have become even more inconspicuous with time. The chimney in the remaining photograph appears to be made of mostly rocks and little to no brick which would have left behind a more visible footprint in the landscape. Historian and member of Avalonia, Beth Moore, speculates that the Gallup homestead may have been located on her property adjacent to the east side of the preserve. There is an old foundation that exists there, coincidentally located a quarter mile northeast of the Denison Homestead.

Stepping onto the wooded preserve from the West Marine parking lot entrance, strollers are immediately enveloped by brush-lined path. While at first glance it may seem like wild, un-touched nature, this landscape has been overcome by human impact and rich history. Stone walls dot the landscape, demarcating the areas where 17th and 18th century farmers cleared away the plentiful rocks in the ground in order to create pastureland for their livestock. These farmers most-likely raised sheep and cattle, as the glacier-molded soil was much too rocky to grow crops for agriculture. New Englanders often joke that the best crop that New England soils can reliably produce every year are rocks. Glaciers covered much of North America and certainly New England approximately 12,000 years ago and brought massive amounts of rock, boulders, and other glacial till with them as they advanced south to eventually form the moraines known as Cape Cod and Long Island. Every year, once the ground freezes and thaws, new rocks pop up to the surface. When Benjamin Franklin visited Stonington, he commented on how appropriate the name “Stonington” was, as he had never visited a place with so many rocks!

The stone walls throughout the preserve reflect the practical mindset of the farmers — larger, base rocks were placed at the bottom with progressively smaller rocks building up to the top. These walls stretched to approximately waist height of an average man at the time of their construction, the highest extent to which these heavy rocks could be lifted. The walls are therefore fairly uniform in height throughout this preserve and similarly throughout all of Connecticut and New England. There are also clear breaks in the walls with larger rocks on either side, marking the cart tracks and cattle pathways. The old wooden poles that remain standing in the ground are reminders of the gates that once occupied the space. The walking trails that wind through this preserve are a mixture of these original “roadways” used by the farmers, natural deer paths, and a few are maintained by Avalonia to ensure clear travels. When looking closely, one may come across a flat slab of rock jutting out of the ground near a wall or at the edge of an old pasture. These have obviously been manipulated by humans and are most likely wolf-stones that were placed over a recently buried body to prevent wolves, or any other animal from digging it up. The connection between natural formation processes and human manipulation past and present is tangible while walking through this preserve.

The vegetation that grows throughout the preserve has much to reveal about the land’s history and certainly looks nothing like it would have a few hundred years ago. The plants growing here now are characteristic of the disturbed, successional habitats that are common throughout New England. After decades of manipulation by farmers including deforestation for pasture land and timber, grazing animals, and quarrying rock, this land has been completely reshaped. Much of the native vegetation that originally occupied the area, such as Oak and American Chestnut trees has been lost. While there are some red cedars, Juniperus virginiana, a common native species that often occupy disturbed habitats, they are still very small and young. The landscape has been taken over by numerous invasive species of plants such as oriental bittersweet, Japanese honeysuckle, swallowart, greenbriar, and autumn olive just to name a few. These changes are clear indications of the continuous human activity that has taken place on the land after the arrival of the colonists. However, we cannot neglect the fact that the original, Native American occupants of the land also played their own role in transforming the landscape.

The “nooners” or large, old trees that are found along the walls provide windows into the past and show what the forest might look like had the majority of it not been cleared out for farmland. The walls were strategically built around these trees so that farmers and their animals could relax on the edges of the fields in the shade and protect themselves from the afternoon sun. In Connecticut, trees found along stone walls in this manner tend to be oaks or ashes. They are by far the oldest trees on the preserve at around two hundred to three hundred years old which is reflected by their large trunks and broad stretching branches. The contrast between the nooners and the surrounding, ragged, younger vegetation that now cover the once pastureland is quite evident when observed through a critical lense.

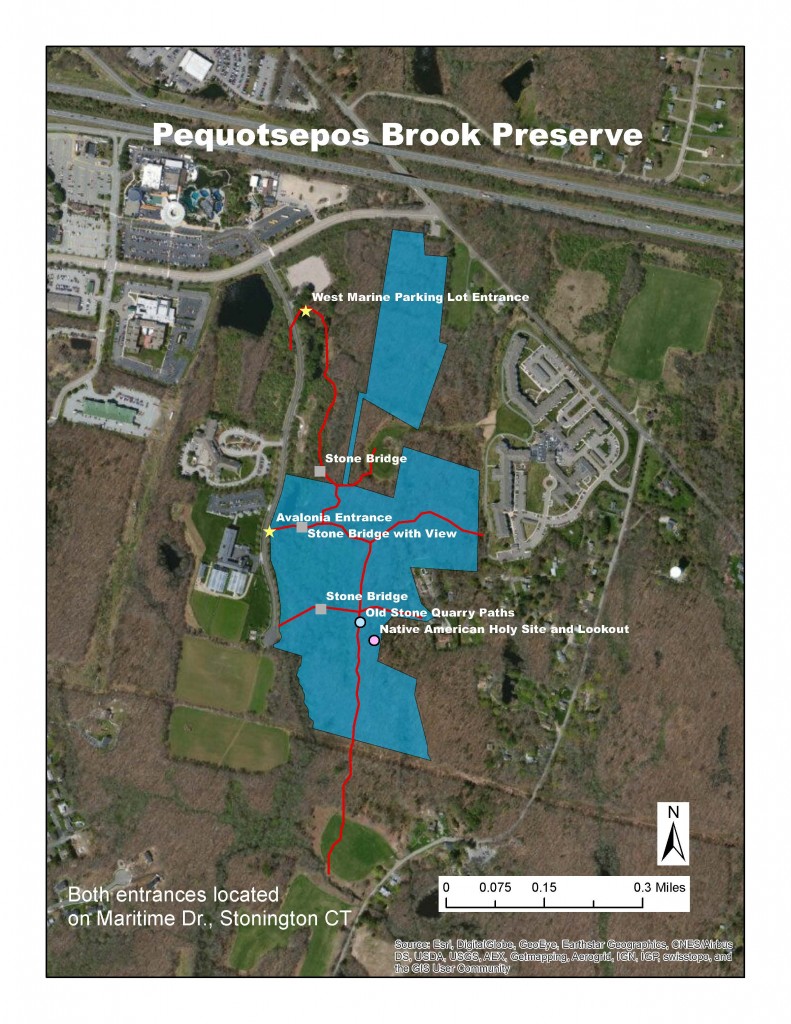

The small brook that runs through the lowlands on the west edge of this property gives this preserve its name. The word “Sepos” actually means brook in the Pequot language which makes for a redundant use of the English word, “Brook” in the name of the property. Three beautifully crafted stone bridges, cross this small brook as continuations of the historic trails that meander through the site. These have been craftily constructed to have very smooth, flat surfaces while allowing to water to flow through, unimpeded underneath and provided another use for the large rocks that occur all over the site. The skill that was put into their construction is reflected by their ability to remain intact and sturdy for over a hundred years. These stone bridges are just wide enough for a farmer’s cart to drive over. Avalonia has done some maintenance on these bridges to clear off any overgrowth and debris that has accumulated with time. Some locals may remember “Plymouth Rock,” a nickname given to a Plymouth car that veered off the road in around 1940 and rolled down into Pequotsepos Brook, over which these stone bridges are found. While it became a landmark of the preserve for some time, it was polluting the brook. In 2013, Paul Gleason of Dean’s Auto Recycling, his son Jim, and employee Frank volunteered to hand-carry, piece-by-piece, the rusty wreck from Pequotsepos Brook to prevent any further pollution and reinstate the natural landscape.

Aside from the farming practices that shaped the preserve, the landscape also has much to reveal about the quarrying that took place in the 1800’s. A few of the pathways and roadways that had already been created and used by the farmers of the previous century were now used to cart various types of rock that were mined near the south end of the preserve. These areas become evident where the excess quarried rock has been set down to line pathways throughout the property. Quarried rock has characteristic jagged edges formed by the cuts of tools used to break apart the rock and may not have as much lichen growth as other, older rocks in the area might due to the recent disturbance. There is also a large, round quarry pool in the high rocks near these pathways.

The large cliff-like features in the southern part of this preserve from which rock was resourced provide more indication of New England’s glacial past. As the glaciers moved south, they scraped out the land and left behind the rock that would not budge, with sides facing the west and east. A Native American specialist who analyzed this preserve hypothesized that these features may have been Native American holy ground because of their west-east orientation which provided an ideal lookout spot when hunting and watching the sun set. Sure enough, at the top of these “cliffs” there is a circle of stones covered in large lichens indicating that they have sat this way for a very long time and could be an anthropogenic feature. The different rock types that make up this circle also indicate that they could have been moved to this location by Natives to point towards the setting sun. There is another potential Native American holy spot further down the path where there appears to be a second, larger stone circle. One of the rocks making up this feature has a certain shape that makes it appear to be a large turtle peeking its head out of its shell. Turtles are sacred to the Pequots (and many other Native tribes) and a rock of this shape may not have gone unnoticed.

In more recent years Avalonia has engaged in some battles over land rights and violations in order to preserve this piece of land. In the 1980’s Avalonia underwent dispute with the Maritime Park Associates who wished to build a subdivision at the intersection of Jerry Browne Road and Pequotsepos Road. The Land trust was concerned about the sensitive wetlands that ran entirely adjacent to the proposed subdivision which could be greatly affected by the construction. Finally in 1988, after years of battle, the Maritime Park Association granted a forty acre parcel of land which now makes up Pequotsepos Brook preserve to the Avalonia Land Conservancy, then known as the Mashantucket Land Trust, Inc.

Most recently, the Mystic Aquarium sold the north lot that contained the trail head to the combined trail system, to West Marine Supply store. After much discussion, the new owners agreed to maintain the trail head entrance and allow public access. There were further negotiations regarding the type of surface used for the parking lot, the water runoff basins and type of vegetation to be allowed to remain in a native state to provide a buffer for the wetlands. Around the same time, Avalonia volunteers created a new entrance off Maritime Drive with a set of steps and bridge to cross the streambed.

The Mystic Aquarium also owns a parcel of land adjacent to the land owned by the West Marine store, and Avalonia maintains the east portion of this land as a non disturbance easement. Avalonia serves to oversee and protect this portion of land so that the Aquarium and any future buyers or developers are not allowed to develop or disturb it. Additionally, Avalonia maintains trail markers throughout the preserve so that the residents of the Stone Ridge senior living community nearby can enjoy a daily walk through the land.

In addition to Pequotsepos Brook, Avalonia protects and maintains multiple preserves for various conservation, historic, and aesthetic purposes. Their contribution to the local community does not go unnoticed and directly impacts neighbors who benefit from the beauty and diversity that the land provides. Without Avalonia, there would be no one to speak for the land and the habitats dependent upon its existence. We hope that this history encourages readers to be inspired by the stories the land has to tell, the services it provides, and the impacts the Avalonia Land Conservancy has on the community.

Bibliography

Denison Pequotsepos Nature Center Website. “What is Coogan Farm?” Denison Pequotsepos Nature Center. Web. Accessed April 24th, 2015. http://dpnc.org/coogan-farm-maps/

Gallup Douglas J. The Genealogical History of the Gallup Family in the United States: Also, Biographical Sketched of Members of the Family. Press of the Hartford Printing Company. 1898. Pg. 21-22

Oaks, Rensselaer A. Genealogical and Family History of the County of Jefferson, New York: A Record of the Achievements of Her People and the Phenomenal Growth of Her Agricultural and Mechanical Industries. Volume 2. Higginson Book Company, Jefferson County, NY. 1905. Pg. 1246-1247.

Whittemore, Henry. Genealogical Guide to the Early Settlers of America: With a Brief History of Those of the First Generation and References to the Various Local Histories, and Other Sources of Information where Additional Data May be Found. Genealogical Publishing Com. 1898. Pg. 203